People are the new platforms

Share On

In web3, platforms succeed by becoming protocols—which means people succeed by becoming platforms.

David Phelps is a 2x founder, a cocreator of ecodao and jokedao, and an investor in web3 projects through the angels collective he started, cowfund. Find him on Twitter at @divine_economy.

Conceived, outlined, and edited by Jad Esber, Nir Kabessa, and David Phelps; written up by David Phelps.

***

There is perhaps no more cringe combo of three words.

But—god help us all—Zuck is right:

“I’ve talked a bunch about how I think that we should design our computing platforms around people rather than apps and I guess that’s sort of what I’m talking about.

On phones today, the foundational element is an app, right? That’s the organizing principle for kind of your phone and how you navigate it.

But I would hope that in the future, the organizing principle will be you, your identity, your stuff, your digital goods, your connections, and then you’ll be able to pretty seamlessly go between different experiences and different devices on that.” — Interview with Ben Thompson

However out of touch with reality he may sound, Mark Zuckerberg is, unfortunately, very in touch with his newly branded metaverse. Let’s note that on three counts.

First, Zuckerberg senses opportunity in fragmentation to lay the tracks of the online railroad—an “organizing principle” that will apply universally across the internet and potentially all computers. The internet, we could say, is still running in a fairly agrarian economy, as that most precious digital commodity—data—is consigned to the localities of individual platforms: Spotify, YouTube, Twitter, TikTok, and, yes, Facebook. The metaverse, Zuckerberg suggests, is a railroad between these local economies that lets them exchange data with the user’s permission. But just because the user has rights does not mean that they have financial upside. Zuckerberg’s railroad is also, after all, a toll.

Second, even as Zuckerberg wants to lay the rails to make data universally transmissible across platforms, he also wants to make data collection, control, and communication even more fragmented. The basis for a new internet, Zuckerberg hints, is a kind of back-closet storage bin, overstuffed with forgotten sweaters and discarded posters of our favorite bands: “your identity, your stuff, your digital goods, your connections.” Zuckerberg understands that in web3 fragmentation is inevitable, as users come to own and manage their data and metadata management—even if, in the world of Meta, they’re not quite able to monetize it. After all, people still need to manage their own data not only to cart it contiguously from one platform to another but in order to experience a metaverse uniquely tailored to the the proclivities of the individual taste, skills, and social networks. Our experience of the metaverse, Zuckerberg suggests, must be individualized to the individual.

At first glance, these two principles—for an internet of completely universal standards and an internet of completely individual standards—might seem to be in conflict. But note Zuckerberg’s key word here: the real purpose of both is to move from device-to-device, world-to-world seamlessly. To move seamlessly in our own private metaverse, we need a universal catalog of all available experiences to give us personalized options. These two principles of a universal internet and a fragmented internet, in other words, are fully codependent. For each is based around the same premise that it’s individuals who take the place of platforms in aggregating and conveying data—with each other and with the platforms themselves.

All three points, in other words, come down to a much simpler one. When people own their own content, including its data and metadata, they own its distribution as well. They become the new intermediaries.

People become the new platforms.

I.

Then again, we might say that people are the old platforms: after all, the internet was founded as a p2p network of individuals working not only to connect to each other, but to connect each other to each other (hence early chat rooms). So why would web3 return us to this seemingly antiquated model after web2’s hegemonic consolidation of winner-takes-all platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram?

To see what’s radically different between web1 and web3, consider the example of Brave Browser: advertisers pay the browser’s users to watch ads through Brave’s native token, with users making more than twice as much revenue as Brave itself. Users take the place of the traditional ad platform, even as they’re directly incentivized to share Brave itself as newfound token-holders. It’s one thing for users to connect their network to new platforms, as in web1—it’s another when they have the incentives to do so.

So by letting people meaningfully own digital content for the first time, web3 doesn’t just shift ownership away from platforms towards their users. More significantly, it incentivizes users to become content distributors as well—to become, well, platforms themselves.

All of that might sound like an exclusionary landgrab for the internet, as if web3’s crypto-nouveau-riche were hoping to leverage their money vaults of $DOGE for that greatest of contemporary powers: the power to shill their bags. This narrative makes it easy to understand why people are the new platforms. What matters most in web3 is our personal voices, the louder and more subjective the better, to sell ourselves and our portfolio.

Let’s run with this narrative for a moment. Web3, here, just adds financial incentives to the internet’s longer-standing social ones. The promise of online identities, pliant shadows of our clunkier physical selves, has always lain in our ability to manipulate them for social and financial capital; hyperfinancialization, in this narrative, just becomes an added incentive to larp, to build the most successful-if-not-always-true version of oneself that one can. Web3 incentivizes us, in other words, to be prominent voices of thought and empathy, the better to become prominent shills.

But here we need to acknowledge a countervailing narrative. Web3 doesn’t just incentivize people to promote narratives by giving them open-market opportunities to buy and sell; it gives them the tools to promote narratives in place of centralized marketplaces that would have traditionally served as the toll-keepers for discovering items and information online. For as important as the incentives for shilling information are, they’re born out of the foundations of distributed ledgers to acquire, understand, and, yes, share this information in fully decentralized ways.

Take, for example, Dune dashboards: anyone can create a dashboard aggregating on-chain data to showcase the relative financial success of different projects. Being good at analytics is the new way of being good at promotion. Everyone becomes an advertiser. Or take The Graph. Users can stake The Graph’s own token as a vote to “curate” their favorite projects—signalling that they’d like indexers to index data for these projects. We’re no longer just incentivized to share information, but now have the tools to incentivize others to get us the information to share. Everyone becomes a marketing agency.

The reclamation of hyperfinancialization for ourselves, then, is simply a logical conclusion of disintermediating legacy players that have long dictated how we’re perceived on the internet, and how we perceive the internet itself: what information is surfaced and what items we’re told to buy. In web3, we decide these ourselves.

But taking data into our hands in terms of how we see it, manage it, own it, and financialize it—this is still only web3’s first step, its opening gambit. The next step isn’t merely offering tools for users to track information, but to develop it, to create their own protocols for making contributions and receiving rewards on-chain. Uniswap is one example here: anyone can become a liquidity provider to earn the majority of value in place of traditional market makers. Of all the “Ubers of [random industry]” pitches from the past decade, Uniswap is arguably the Uber of Wall Street, letting anyone populate its marketplace, with a twist that LPs don’t form the supply side of a transaction but enable the transaction itself. Users are the marketplace. Uniswap points to the increasing power of individuals not just to build out platforms like Dune or The Graph but become platforms themselves.

In other words, the next step is not giving users ways to aggregate existing types of data, but to mediate and collect new forms of data altogether.

Or more simply, the next step is giving users ways to build their own platforms.

II.

And in that sense, web3 marks both the culmination of a past decade of user-generated creation that has seen the cost of code fall dramatically as well as the inception of permissionless building. Together, these two trends are what unlock this next wave for people to become their own platforms.

First, the cost of code is low. For all its promise of degen 14 year olds coding billion-dollar defi protocols, web3 is, in some ways, a culmination of the past decade of no-code solutions. Because smart contracts are open-source, anybody can use or modify them; basic financial functions like splitting income among multiple parties that would have required months of dev work with Stripe can now be performed with a split contract in a few minutes through a site like Mirror.

In other words, open-source protocols accelerate innovation by letting anyone build, so that with proper financial incentives for creators, they can quickly take the place of closed web2 protocols. That makes it hard for platforms to extract value, however, since open-source environments let anyone fork the platform and redeploy it with lower commissions to attract consumers: this is famously what SushiSwap did to Uniswap, forking the protocol to offer extra fees to users, and what Hive users did to Steemit after frustration from Tron’s takeover. So the real winner here is the individual consumer. Platforms lose their moat when others can hard-fork them in cheaper, community-run versions, and consumers win with lower fees.

But here’s where it gets interesting. Let’s remember that the individual consumer is also someone who’s able to build out the platform in a low-code environment—and incentivized to do so by holding a token. Smart contract composability, the premise that one smart contract can call on the data and functions of another the way a DJ might remix another artist’s work, is typically understood as software legos: the ability of one dev to build on another’s code.

The implications, however, redefine business as we know it. After all, companies no longer need to build code from scratch in siloed environments when they can draw on each other’s work. More to the point, companies no longer need to exist when individuals can just build on top of each other’s work for cheap. As we’ve seen with Rari, a DeFi aggregator built by teenagers with over $1B in TVL, anyone with a computer and a bit of dev experience can—in theory—create a protocol.

And this is the point of our second trend: it’s easier than ever to make content when that content is participatory/responsive to other content and built on top of it, whether through subtweets, TikTok responses, hard-forks, or composable smart contracts. In short, the shifts we’ve seen play out over the past decade in the creator economy are now transpiring in tech. Just as the rise of influencers and fall of corporate legitimacy left individuals to become the primary distribution for brands and eventually to form their own (Tyler, Rihanna, even George Clooney), a few individual devs can take the place of entire corporations in building decentralized financial rails.

And just as fans have increasingly become creators by recomposing creators’ work on platforms like TikTok, users of DAOs and protocols are increasingly their workers as well, helping build out their communities and code as composability dissolves the lines between consumption and creation.

All of which explains how people can become their own platforms. But the deeper question is: dubious tokens aside, why would they?

III.

Who are we online? Well, up until now, we’ve left breadcrumbs of who we are across siloed platforms: our music preferences on Spotify, our favorite restaurants on OpenTable, our professional self lives on LinkedIn. Basically, we’ve been mini-piles of data in the image of each platform we use, able to express ourselves only so far as the platform would let us—like bowls of ingredients that have never been combined to make a dish.

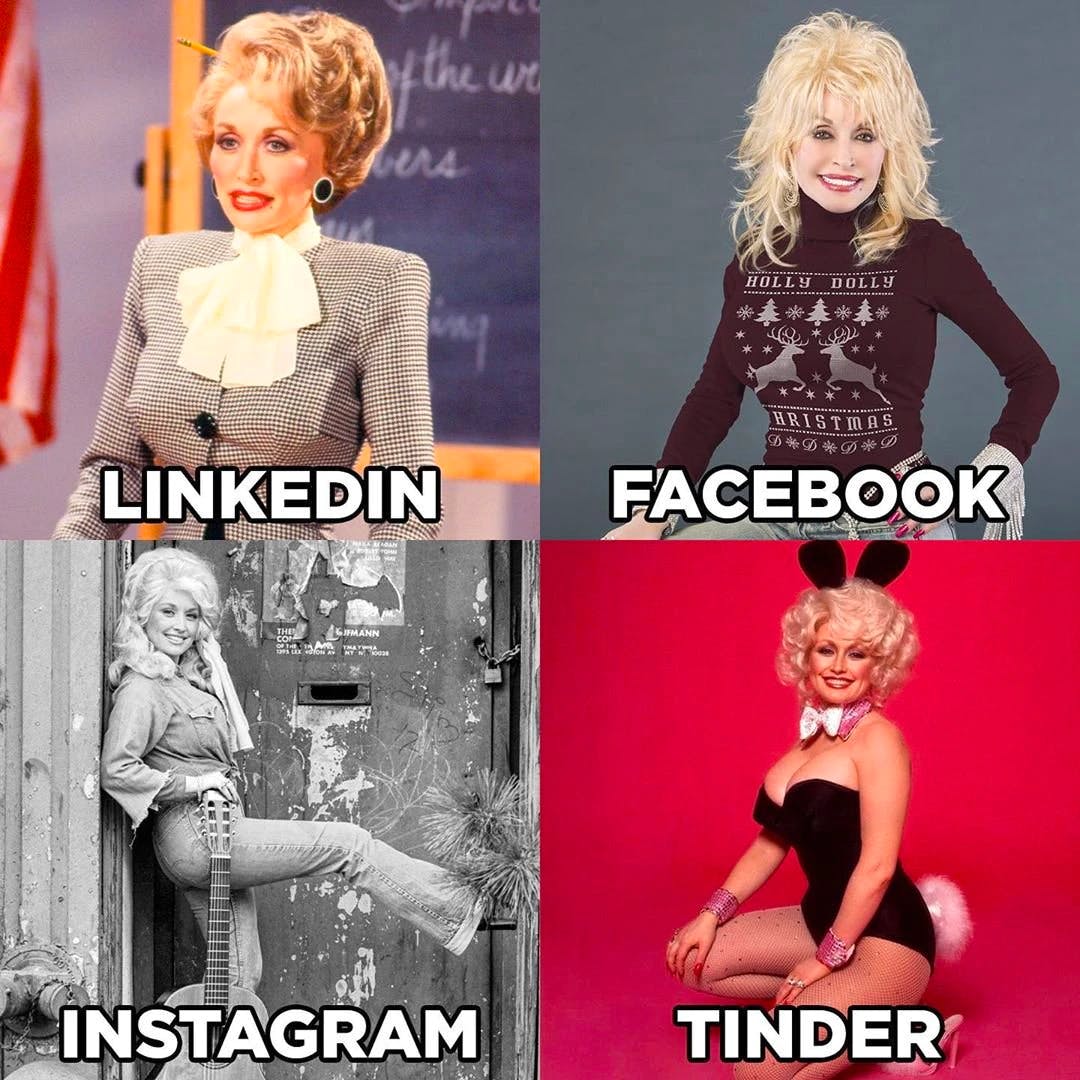

We’ve had to split our identities to fit the contexts of different platforms, a kind of hyper-actualization of our tendencies (and instincts) to adapt who we are in different physical spaces and communities. We might see the fundamental promise of the internet here—that we can explore ourselves online without fear of scrutiny or judgment. To paraphrase Marx, we might hunt for jobs on LinkedIn in the morning, fish for compliments on Instagram in the afternoon, criticize each other on Twitter after dinner, and be as lascivious as we like on Tinder in the late evening, without letting any of these identities define us.

Nevertheless, something is lost in this fractionalization of the self into a series of performance pieces—not only in the division of ourselves into separate entities, but in the ways we construct ourselves according to the limited mandates of each platform.

On the simplest level, web3 can allow us to “bring our whole selves” to platforms without fear of scrutiny or judgment by aggregating our online data and sharing the parts we find relevant to receive better recommendations and find better opportunities. Web3 enables us to traverse all these spaces and carry this identity—in the form of an address with on-chain data—across them while having control to share those parts of ourselves that we choose.

To put this in web2 terms, you might use the data from the videos you watch on YouTube to help determine the music you would like on Spotify—and you might choose to share that data with advertising protocols as well to earn directly from ads relevant to your taste and needs in the ways that social media platforms have always done on your behalf. (Indeed, the benefits of cross-platform data aggregation help explain Google and Facebook’s success not for any given product, but for collating products across our professional and personal lives). Adult entertainment platforms will likely be some of the first to harness web3 curation, not only because decentralization can relieve users’ fears of corporate surveillance that prevent them from sharing more data currently, but because that data can be used to deliver more targeted results for different users.

But more importantly, web3 can let us transcend the limited language of existing platforms by creating more advanced living, breathing identities on-chain. Our data doesn’t need to be limited to our music selections or our conversations with strangers on dating apps. It can include our contributions to building communities in DAOs, to writing articles that others draw on and quote, to our success in promoting others around us. For better or worse, it will increasingly include biometrics as well—cortisol levels, blood sugar, heartbeat, how we make eye contact, how we smile, how we walk. The point ultimately is that it will showcase who we are not simply as checkboxes of consumer taste, but active creators, contributors, and collaborators—as humans.

The real promise of data ownership, it turns out, isn’t simply that we can store, monetize, and share data ourselves. It’s that the incentives to do so will also incentivize us to track more advanced and individuated data than ever before. In the short run, that data will let us replicate our offline identities on-chain as we showcase our personal skills and accomplishments. In the long run, that data will let us automate our online behaviors, from writing emails to making investments, as we shift from online actors to online curators, merely confirming the actions we want our online selves to perform.

And in the longest run, we’ll be able to create versions of ourselves online that are no longer skeuomorphic approximations of our offline selves, but collective creations—selves that may write emails for us based on collective data, perhaps, or even selves that communicate with each other without any need for email at all. Perhaps, ultimately, we’ll become their creations, as they redirect our own everyday actions based on the data of those similar to us so we can better optimize our time.

And ultimately? We may end up back with multiple versions of ourselves, various characters in the giant RPG that is being online: the job-hunter, the compliment-fisher, the critic, the flirt. But these versions of ourselves won’t be tied to specific platforms. They’ll be full-fledged creations, alts that enable us to become new people both online and off. Instead of assuming whatever identity Linkedin, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter preformat us into, our online identities will become Linkedin, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter themselves: data aggregators that take on identities based on the data of those closest to us and help shape their identity in turn.

At that point, we’re not so far from who we are in real life, creators and creations of the social constructs around us. This is why becoming our own platforms is so powerful, so promising, and potentially a bit perturbing as well.

IV.

Back in 2016, Joel Monegro proposed the central difference for building businesses on blockchains vs. the internet: on the internet, platforms like Google and Facebook capture value on top of largely valueless open-source protocols (TCP/IP) whereas on distributed ledgers, the protocols themselves capture value in the form of a state-like currency that reflects the GDP-like value of the applications being built on top of it. The catch, for Monegro, is that blockchain applications on top of protocols struggle to accrue value themselves—not just because they’re open-source, interoperable, user-owned, and don’t own their own liquidity, but simply because users will invest in the underlying protocol in order to invest in the applications on top. So value accrues to the protocol’s token that applications use.

Years later, every application has their own damn token, with two consequences that might seem to threaten Monegro’s thesis: first, value *can* accrue at the platform level through its own currency, and second, having far more tokens with far less value means that there are real switching costs for moving from one platform to another as liquidity vanishes. They may represent fleeting victories, but Uniswap and OpenSea are both stories of conquering liquidity of micro-micro-caps.

So much for the fat protocol thesis, we might say. The platforms of web3 start to look a lot like the p2p platforms of web2 and web1: the Pipes, the Airbnbs, the Ebays that win markets by capturing liquidity for rare, non-fungible items and services, their strong liquidity moat giving them strong commissions.

But there is a difference. Because: to get users in the first place, platforms have to increasingly airdrop their token that incentivizes users not only to use the platform, but more importantly, grow its long-term value by getting their network to use it as well. No self-respecting platform under the watchful eyes of the SEC would say that they’re user-owned, exactly, but the fact that platforms have to give up a marketized share of governance to their users tells us what’s so revolutionary about web3. The users and management are no longer on opposite sides of a transaction but deeply aligned. In some sense, the platforms belong to the people.

And what if users dump the token for a quick eth or two? A token can acquire a user, but it can’t retain them—for that, users have to collectively decide that the project and the token are actually worth something to them practically, socially, and emotionally. The real value is determined by social consensus of users coming together to prop up a token’s value just enough to incentivize others to care about the project too. Even public markets don’t operate this way, with the speculators generating usage rather than users generating speculation. The value is truly in the hands of the people.

But there’s one final opportunity that remains untapped, the stuff of the next few years. Users don’t simply control their data on web3 platforms—their tokens, their contributions, their social records—but will increasingly have ways to leverage that data as on-chain credentials for joining emergent communities, testing their predictions, and getting jobs. Platforms’ secret opportunity is in incentivizing collection of this data for users to leverage. This may sound counterintuitive when platforms don’t own users’ data in web3, but there are two underlying points.

First, platforms have an opportunity to build an underlying social graph of unique data and then to self-cannibalize by letting other platforms draw on it: the real financial opportunity for every platform, in other words, is to become a protocol that others build on top of.

And second—at least in theory, if not always practice—the platforms are not much greater than the sum of their users. Because it’s the users who govern the platforms, own its token, and even use platforms to transact in the token.

So what we ultimately see is a kind of downleveling of web2 structures: platforms all become protocols, and people create their own networks on top of these new protocols.

Or if you like: people become the new platforms.

Comments (5)

Art K@art_k2

I don't think I understand all of this, so my questions may seem dumb.

If my knowledge is mine, which it is,

how can I get on Web3,

what kind of 'site' can I build

how I can get people to find me

Share

I need your help

For sure it's my fault but I didn't get the difference between web1 e web3

More stories

Sanjana Friedman · Opinions · 9 min read

The Case for Supabase

Vaibhav Gupta · Opinions · 10 min read

3.5 Years, 12 Hard Pivots, Still Not Dead

Kyle Corbitt · How To · 5 min read

A Founder’s Guide to AI Fine-Tuning

Chris Bakke · How To · 6 min read

A Better Way to Get Your First 10 B2B Customers